History Compression via Language Models in Reinforcement Learning

This blog post explains the paper History Compression via Language Models in Reinforcement Learning (presented at ICML 2022).

HELM (History comprEssion via Language Models) is a novel framework for Reinforcement Learning (RL) in partially observable environments. Language is inherently well suited for abstraction and passing on experiences from one human to another. Therefore, we leverage a frozen pretrained language Transformer (PLT) to create abstract history representations for RL.

To use a PLT for history compression we have to translate environment observations to the language domain. To this end, we introduce the FrozenHopfield mechanism. The key feature of the FrozenHopfield is that it does not require any training. Thus, we avoid propagating gradients through the huge Transformer model. Therefore, no samples are required for finetuning the PLT. This makes our approach very sample efficient.

The HELM framework

Our proposed framework, HELM, as depicted below, consists of three main parts:

- History compression via FozenHopfield and PLT

- CNN trained for encoding the current timestep

- Actor-critic head trained for policy optimization

We instantiate the PLT with a TransformerXL (Dai et al., 2019), which strikes a reasonable balance between performance and complexity. We utilize a CNN based on the small Impala architecture (Espeholt et al., 2018) since we mainly focus on image-based environments. Finally, we utilize an MLP with one hidden layer for the actor-critic head. The only trainable components of HELM are the CNN encoder of the current timestep and the actor-critic head.

FrozenHopfield

We solve the problem of translating environment observations to the language domain by the FrozenHopfield mechanism.

It maps any type of observation vector to a suitable token embedding.

FrozenHopfield utilizes modern Hopfield networks to associate observations with stored token embeddings.

It leverages the Johnson-Lindenstrauss (JL) lemma which guarantees that random projections preserve mutual distances between datapoints to a large extent with high probability.

The JL-lemma justifies the use of a random but fixed projection of observations.

The FrozenHopfield mechanism uses these projections as queries to retrieve a convex combination of stored token embeddings.

The retrievals live in the language domain and are therefore well-suited as inputs to the PLT.

More formally, let \(\BE = (\Be_1, \dots, \Be_k)^\top \in \dR^{k \times m}\) be the token embedding matrix from the pretrained Transformer consisting of \(k\) embeddings \(\Be_i \in \dR^m\).

Further, \(\BP \in \dR^{m \times n}\) is a random projection matrix whose entries are independently sampled from a \(\cN(0, n / m)\) normal distribution.

The variance \(n / m\) is required by the JL lemma.

At time \(t\), we obtain inputs \(\Bx_t \in \dR^m\) for the Transformer from observations \(\Bo_t \in \dR^n\) via the FrozenHopfield mechanism as in the figure below.

The inputs \(\Bx_t\) represent Hopfield retrievals, where \(\BP \Bo_t\) are the state patterns or queries and \(\BE\) are the stored patterns (token embeddings).

Equivalently, it can be viewed as a dot-product attention mechanism with query \(\BP \Bo_t\), and keys and values \(\BE\).

Since the inputs \(\Bx_t\) are in the simplex spanned by the stored patterns \(\BE\), it is guaranteed that \(\Bx_t\) lies in the convex hull of the set \(\{\Be_1, \dots, \Be_k\}\).

Therefore the Transformer only receives inputs lying in the realm of the embedding space where it was pretrained on.

Results

We compare HELM to an LSTM (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997) baseline with a CNN backbone (Impala-PPO, Espeholt et al., 2018) trained from scratch. Further, we add a comparison to a Markovian policy which consists of the small Impala CNN backbone and the actor-critic networks (CNN-PPO).

RandomMaze

First, we show results on a simple procedurally generated random maze environment.

The aim of the agent is to navigate to a goal tile which is located in the lower right corner, while starting at a random position in the maze.

The agent receives a large negative reward for bumping into a wall and a small negative reward for each step.

HELM outperforms both competitors after training for 2M timesteps.

See a few sample episodes of a trained HELM agent below.

Minigrid

We train on the KeyCorridor (MiniGrid-KeyCorridor-v0) environment in which the agent needs to collect a key behind a closed door to unlock another door and pick up an object.

Additionally, the agent has a restricted field of view (light-gray area in the figure below) depending on which direction the agent is currently facing.

Thus, the agent needs to memorize that it had already picked up the key before trying to unlock the door behind which the target object is located.

Again, HELM significantly outperforms both Impala-PPO, and CNN-PPO.

See a few sample episodes of the trained HELM agent above.

Procgen

We tested HELM on the very challenging Procgen benchmark suite, which consists of 16 diverse environments.

Six out of these 16 environments (caveflyer, dodgeball, heist, jumper, maze, miner) offer a memory mode which provides partial observability.

We train HELM, Impala-PPO, and CNN-PPO for 25M timesteps.

HELM significantly outperforms both Impala-PPO and CNN-PPO in 4 out of 6 environments.

The next figure shows the mean normalized scores across all six environments.

HELM significantly outperforms Impala-PPO.

See some sample episodes for miner, maze, and dodgeball.

Analysis of representations

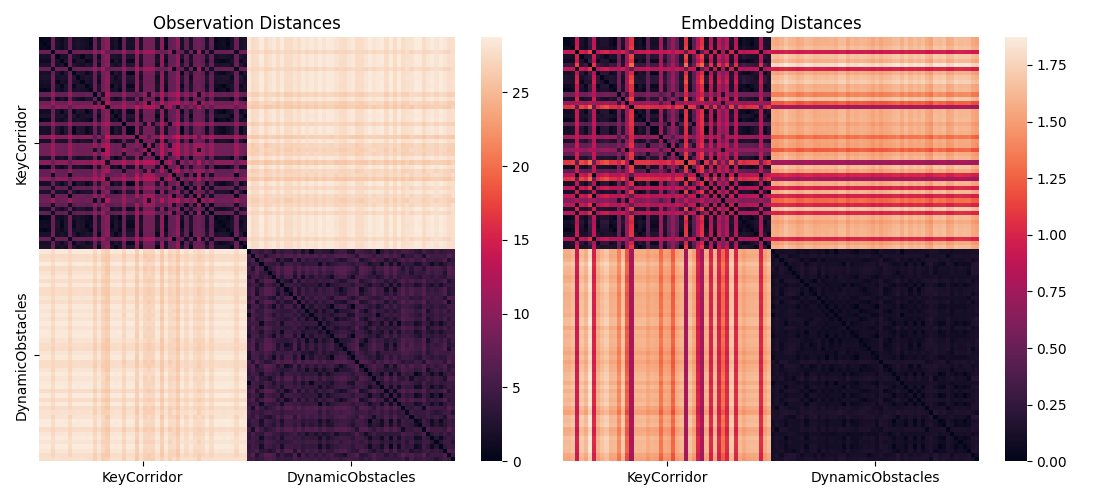

We take a closer look at the abstractions obtained by the FrozenHopfield mechanism and the PLT. First, we show the distance preserving property of FrozenHopfield by looking at two Minigrid environments, namely KeyCorridor and DynamicObstacles (MiniGrid-Dynamic-Obstacles-Random-5x5-v0). The figure below shows distance matrices in the observation space (i.e. input to FrozenHopfield) and the token embedding space.

For \(\beta = 1\) (above) the distances are approximately preserved.

With increasing \(\beta\) we can control the amount of dispersion in the embedding space and additionally enhance the distances to avoid representation collapse.

Moreover, observations that are similar in pixel space map to the similar token embeddings.

For \(\beta \rightarrow \infty\) we can retrieve a single token that represents the maximum contribution to the retrieved token embedding of FrozenHopfield:

In both examples above the agent faces a door.

FrozenHopfield maps these observations to the same word, in this case “recollection”.

Again by varying the \(\beta\) parameter we can control the amount of clustering, which results in different levels of abstraction.

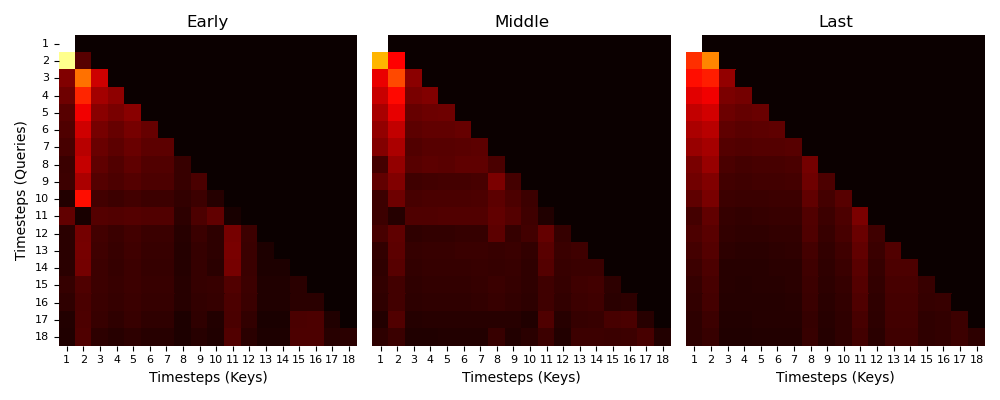

Finally we take a look at the attention maps of different attention heads in different layers of the PLT.

To this end we analyse a trajectory of the KeyCorridor environment and retrieve attention maps of an early, a middle, and the last layer.

We find that the attention maps show similar patterns, all of them attending to the second timestep which is where the agent encounters the key the first time.

Furthermore, most heads attend to timestep 11 which is the first time the agent encounters the ball.

This demonstrates that some attention heads respond to certain key events that are crucial for solving the task.

For more details, please check out our paper.

Material

Paper: History Compression via Language Models in Reinforcement Learning

Github repo: HELM

Contributions by Thomas Adler, Vihang Patil, Angela Bitto-Nemling, Markus Holzleitner, Sebastian Lehner, Hamid Eghbal-Zadeh, and Sepp Hochreiter.

If you have any questions feel free to contact us at this email.